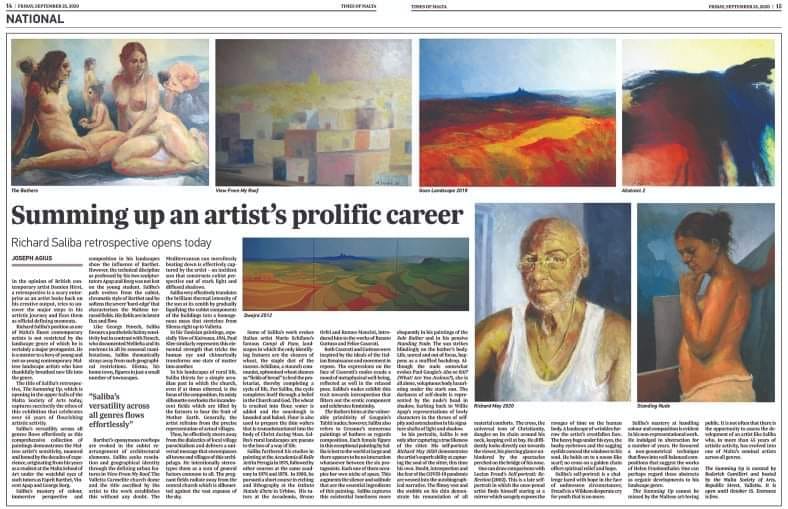

In the opinion of British contemporary artist Damien Hirst, a retrospective is a scary enterprise as an artist looks back on his creative output, tries to uncover the major steps in his artistic journey and fixes them as official defining moments. Richard Saliba’s position as one of Malta’s finest contemporary artists is not restricted by the landscape genre of which he is certainly a major protagonist. He is a mentor to a bevy of young and not so young contemporary Maltese landscape artists who have thankfully breathed new life into the genre.

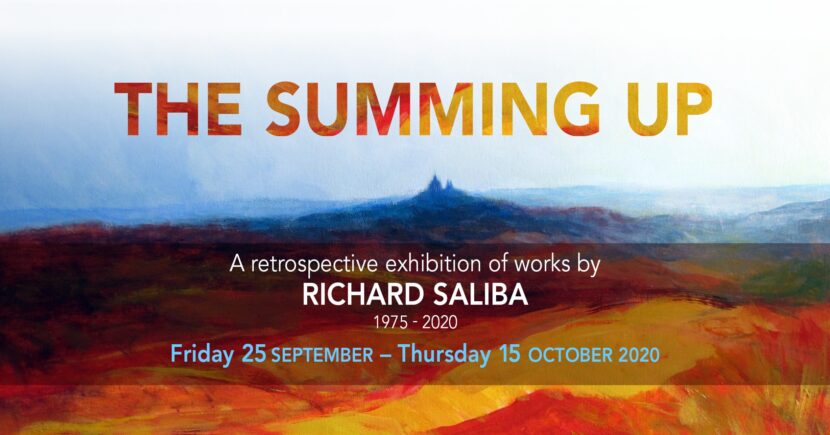

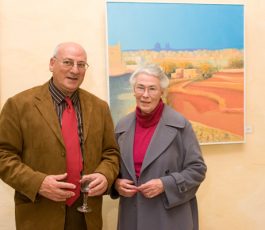

The title of Saliba’s retrospective, The Summing Up, hosted in the upper halls of the Malta Society of Arts captures succinctly the ethos of this exhibition that celebrates over 45 years of flourishing artistic activity. Saliba’s versatility across all genres flows effortlessly as this comprehensive collection of paintings demonstrates the Maltese artist’s sensitivity, nuanced and honed by the decades of experience, originating from his years as a student at the Malta School of Art under the watchful eyes of such tutors as Esprit Barthet, Vincent Apap and George Borg.

Saliba’s mastery of colour, immersive perspective and composition in his landscapes show the influence of Barthet. However, the technical discipline as professed by his two sculptor-tutors Apap and Borg was not lost on the young student. Saliba’s path evolves from the cubist, chromatic style of Barthet and softens the severe ‘hard-edge’ that characterises the Maltese terraced fields. He fields are in latent flux and flow.

Like George Fenech, Saliba favours a pantheistic balmy sensitivity but in contrast with Fenech, who documented Mellieħa and its environs in all its seasonal manifestations, Saliba thematically strays away from such geographical restrictions. Sliema, his hometown, figures in just a small number of townscapes. Barthet’s eponymous rooftops are evoked in the cubist re-arrangement of architectural elements. Saliba seeks resolution and geographical identity through the defining urban features in View from my roof. The Valletta Carmelite church dome and the title ascribed by the artist to the work establishes this without any doubt. The Mediterranean sun mercilessly beating down is effectively captured by the artist – an incident sun that constructs cubist perspective out of stark light and diffused shadows.

Saliba very effectively translates the brilliant thermal intensity of the sun at its zenith by gradually liquifying the cubist components of the buildings into a homogenous mass that stretches from Sliema right up to Valletta. In his Tunisian paintings, especially View of Kairouan, 1914, Paul Klee similarly represents this elemental strength that tricks the human eye and chimerically transforms one state of matter into another.

In his landscapes of rural life, Saliba thirsts for a simple arcadian past in which the church, even if at times ethereal, is the focus of the composition. Its misty silhouette overlooks the incandescent fields which are tilled by the farmers to bear the fruit of Mother Earth. Generally, the artist refrains from the actual precise representation of actual villages.

Thus, he effectively steers away from the dialectics of local village parochialism and delivers a universal message that encompasses all towns and villages of this archipelago. He intentionally stereotypes them as a sum of general factors common to all. The pregnant fields radiate away from the central church which is silhouetted against the vast expanse of the sky.

Some of Saliba’s work evokes Italian artist Mario Schifano’s famous Campi di Pane, landscapes in which the only identifying features are the sheaves of wheat, the staple diet of the masses. Schifano, a staunch communist, epitomised wheat sheaves as “fields of bread” to feed the proletariat, thereby completing a cycle of life. For Saliba, the cycle completes itself through a belief in the Church and God. The wheat is crushed into flour, water is added, and the sourdough is kneaded and baked. Flour is also used to prepare the thin wafers that is transubstantiated into the body of Christ during Mass. Saliba’s rural landscapes are paeans to the loss of a way of life. The spiritual no longer sustains us as we have assigned new gods to determine our fate.

Saliba furthered his studies in painting at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Perugia in 1975, followed by other courses at the same academy in 1976 and 1978. In 1980, he pursued a short course in etching and lithography at the Istituto Statale d’Arte in Urbino. His tutors at the Accademia, Bruno Orfei and Romeo Mancini introduced him to the works of Renato Guttuso and Felice Casorati.

Both Casorati and Guttuso were inspired by the ideals of the Italian Renaissance and movement in repose. The expressions on the face of Casorati’s nudes exude a mood of metaphysical well-being, reflected as well in the relaxed pose. Saliba’s nudes exhibit this trait towards introspection that filters out the erotic component and celebrates femininity.

The Bathers hints at the vulnerable primitivity of Gauguin’s Tahiti nudes; however, Saliba also refers to Cezanne’s numerous paintings of bathers as regards composition. Each female figure in this exceptional painting by Saliba is lost to the world at large and there appears to be no interaction whatsoever between the six protagonists. Each one of them occupies her own niche of space. This augments the silence and solitude that are the essential ingredients of this painting.

Saliba captures this existential loneliness more eloquently in his paintings of the Sole Bather and in his pensive Standing Nude. The sun strikes blindingly at the bather’s body. Life, unreal and out of focus, happens as a muffled backdrop. Although the nude somewhat evokes Paul Gaugin’s Aha oe feii? (What! Are You Jealous?), she is all alone, voluptuous body luxuriating under the stark sun. The darkness of self-doubt is represented by the nude’s head in shadow, harking back to Willie Apap’s representations of lowly characters in the throes of self-pity and ostracisation in his signature shafts of light and shadow.

In his portraits, Saliba is not only after capturing a true likeness of the sitter. His self-portrait Richard( 24th )May 2020 demonstrates the artist’s superb ability at capturing the soul of the sitter, this time himself. Doubt, introspection and the fear of the COVID-19 pandemic are weaved into the autobiographical narrative. The flimsy vest and the stubble on his chin demonstrate his renunciation of all material comforts. The cross, the universal icon of Christianity, dangles on its chain around his neck, keeping evil at bay. He diffidently looks directly out towards the viewer, his piercing glance unhindered by the spectacles perched on the bridge of his nose.

One can draw comparisons with Lucian Freud’s Self-portrait: Reflection (2002). This is a late self-portrait in which the once-proud artist finds himself staring at a mirror which savagely exposes the ravages of time on the human body. A landscape of wrinkles furrow the artist’s crestfallen face. The heavy bags under his eyes, the bushy eyebrows and the sagging eyelids conceal the windows to his soul. He holds on to a noose-like scarf; no cross on a golden chain offers spiritual relief and hope. Saliba’s self-portrait is a challenge laced with hope in the face of unforeseen circumstances, Freud’s is a Wildean desperate cry for youth that is no more.

Saliba’s mastery at handling colour and composition is evident in his non-representational work. He indulged in abstraction for a number of years. He favoured a non-geometrical technique that flows into well-balanced compositions that suggest the works of Helen Frankenthaler. One can perhaps regard these abstracts as organic developments to his landscape genre.

The Summing Up cannot be missed by the Maltese art-loving public. It is not often that there is the opportunity to assess the development of an artist like Richard Saliba who, in more than 45 years of artistic activity, has evolved into one of Malta’s seminal artists across all genres.

The Summing Up is curated by Roderick Camilleri and hosted by the Malta Society of Arts, Republic Street, Valletta and is open till Thursday October 15. Entrance is free.

Joseph Agius

22nd September, 2020